- In 1989, the Taiwanese government decided to adopt open measures for foreign films, in response to the impact that joining the World Trade Organisation (WTO) might cause. Korea and Hong Kong also faced the same issue.

- In 1997, domestic films occupied only 1-2% of the market share in Taiwan. Meanwhile, Titanic became the first film to reach the billion-dollar mark in the world.

- In 1998, fewer than 20 Taiwanese films were produced. Korean directors shaved their heads in a rally asking the government to re-institute screen quotas, encouraging Korean people to support their domestic cinema. The domestic film market share of that year reached 40%.

- In 2001, Taiwan officially joined the WTO. The Legislative Yuan passed the Draft Revision of the Film Law on deletion of the screen quotas and surcharges on foreign films.

- In 2007, the market share of domestic films was less than 1%, while that of foreign films accounted for 99%. Taiwan ranked as 10th largest export partner of American cinema around the globe. American company Warner Village Cinemas opened a branch in Taiwan.

- In 2010, the Taiwanese government signed the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA). China agreed to open its theatrical markets to films from Taiwan. Night Market Hero and You’re the Apple of My Eye made their debut in China. Exported films were also limited to those without political taboos involved.

The data above refers to Lu Fei I’s Inspection of Fifty-year Taiwan Cinema from Numbers.

Around the time of when I was born turned out to be tough times in the history of cinema in Taiwan. In elementary school, my friends and I would gossip about the scene where Rose’s hand slid down that carriage window in Titanic, or our first visit of the newly open fashionable Warner Vieshow to watch Amélie. During the years of senior high, we joined in film clubs learning filmmaking. Double Vision, Blue Gate Crossing, Spider Lilies, and Eternal Summer were released one after another. I remembered the director of our club saying Taiwanese films were having a hard time. I can also recall being enchanted by La Nouvelle Vague. Indeed, when talking about Taiwanese cinema, people have only been able to rap out a list of names; Edward Yang, Hou Hsiao-Hsien, and Ang Lee. I feel so confused about this. Where on Earth are the others? Where are the female directors? Will filmmaking manage to survive the harsh environment?

The sovereignty of Taiwan often serves as a bargaining chip in international trade negotiations. America would take advantage of the tension between Taiwan and China to sell arms or agricultural products to Taiwan, so as to earn their own bargains in negotiations; for instance, the signing of international trade contracts such as WTO, ECFA, and CSSTA. No matter whether it’s antitrust regulations that lead to the dumping of Hollywood films and the collapse of the Taiwanese film industry, or the cross-strait trade agreement that made the national box office promising, Taiwanese films are always seeking their own survival and values in this international background. In response to Taiwan’s stagnating cinema industry, some creators switched to a different target audience, sharpening the artistic elements of their works, and turned to cater for a more Euro-American centric artistic taste.

Taking these geopolitical factors into account, however, one can’t help but question whether the new wave of Taiwan in the 1980s was a success. After signing ECFA, can Taiwanese movies exported to China’s box office be simply marked as successful? And how much do we adopt the “art” of the western view to limit the multiple possibilities of medium of art, audienceship, show field and production techniques? What have we learned from those tough moments?

Cooperation between corporations and governments monopolise trades exporting capital abroad for higher profits. Capitalism, in this sense, represents contemporary militarism. Over the past two years, I’ve been thinking about Taiwan as an empire boundary between China and the United States. As a creator, how could we resist the wave of imperialism with the re-establishment of medium of art, aesthetics, and concepts? Shall we unite to flip the given creation resources and existing forms? And in the face of the inevitable, struggling desire to welcome Euro-American centric elements, still make our own way to achieve creation? Moreover, how can we take art creation as a way of deconstruction to build our own knowledge system, reorganise the niche market, and reorganise our own ideal dialogue objects and dialogue logic?

Since the rise of dialects in the 17th century, which brought about the birth of borders between modern national community, in the 20th century, the contemporary art and Hollywood movies sponsored by the CIA led a group of people to leave their country in pursuit of the value of the open, free American dream. Then, to establish a visual articulation of Taiwan under this imperial background can appeal to what kind of people to see another utopia?

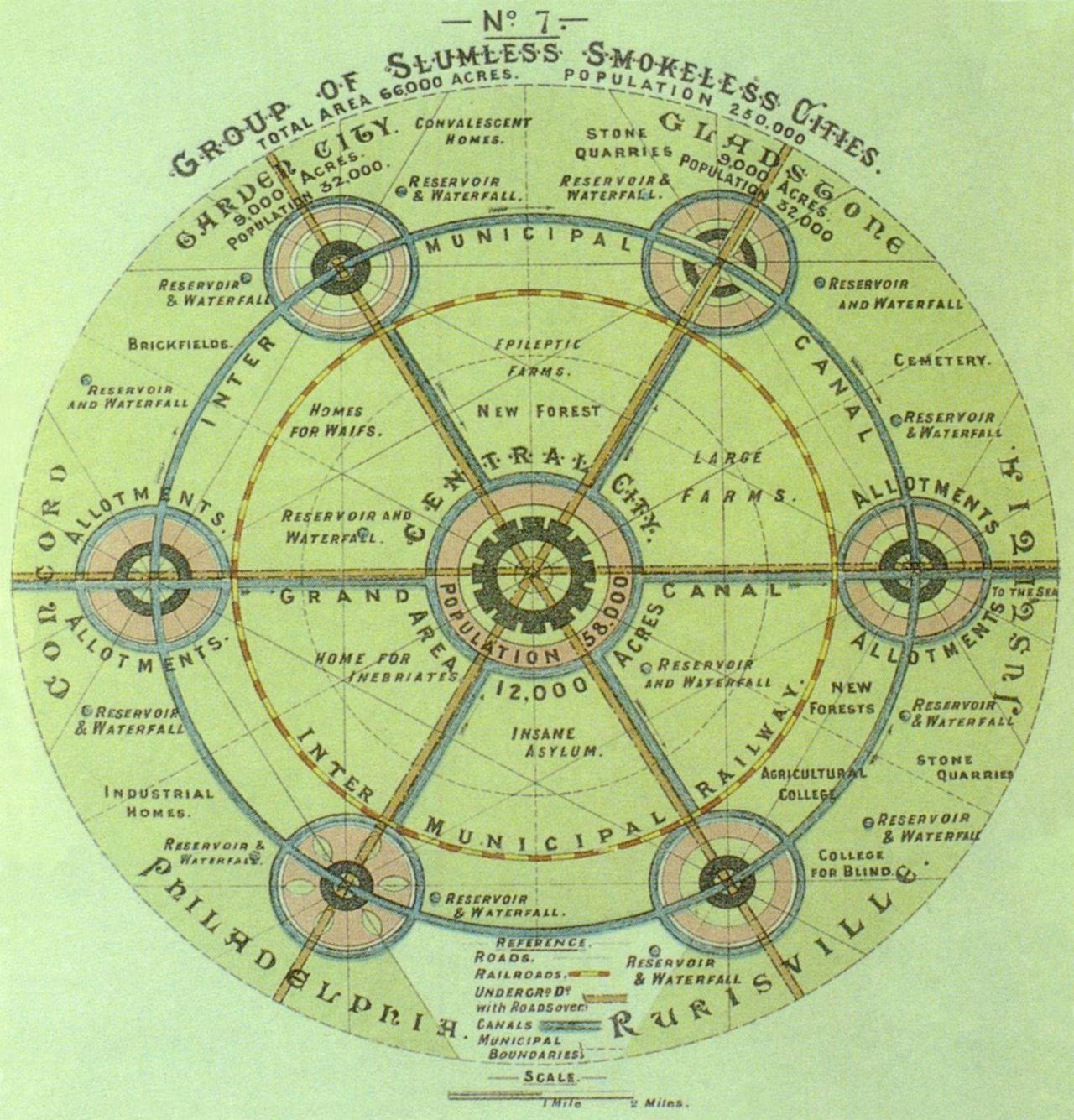

In this regard, we need to form our own visual articulation beyond the idea of western centrism as a colonisation and a representation of our voice. One of the ways is to review the industrial contracts carried out by the view of mainstream films. What is the “view”? Suppose a new city is to be built in a certain place in Taiwan. To do the urban planning, the designer may take a plan of New York’s chessboard-like street as a model for the construction of this new city. Now, the designer seems to be copying the plan from above to the land from an omniscient point of view, and, to complete the “ideal” city, they would introduce the scale of American buildings and the underground pipeline configuration. Local people’s lifestyle, nevertheless, may be completely unfit for this kind of city. After years of spontaneous population growth and development in the city, new apartments would be asked to be built in some parks, mixed-use districts would gradually develop on some over-crowded streets. (The urban planning of Yonghe District, New Taipei City as an example.)

This “preview/copy” logic also applies to the film industry. When the Euro-American centric visual aesthetics are transmitted horizontally on a large scale, the labor (cinematographers, gaffers, production designers), and the tools (cameras, lights) of their visual production also need to be exerted. What kind of depth of field, resolution, what kind of movement, lighting, and on-site arrangement once again help with the overall export of the imperial industrial chain, so as to achieve “the ideal picture” and “the texture a film should have”? In order to create certain scenes, tools used such as the huge cameras, cranes, platforms, the male-dominated labor force, and the highly-integrated funds also limit the gender composition and the threshold of film production.

Reflecting upon the “preview” logic, we’ll need to pay attention to the organic nature of the “production process” and “regard the process as a purpose.” Up to the present, even though women make up 52% of the total audience, men represent 92% of directors. 80% of female directors only get to make a film over ten years. This also means that the audience is now watching things through the eyes of men, perceiving and interpreting their own lives through the contents of these films. So we might well put this kind of gaze aside and rethink what kind of machines can women use, or what kind of vision can they produce. In contrary to the “male gaze” in the past film industry, what difference in the world do queers see? How would the elders make use of their eyes? What sort of stories are important for the aboriginal tribes? Whom shall we tell these stories to?

This way, visual output of each ethnic group and their figure appears as an indigenous unit. Even online streaming, mobile phone selfies, desktop images, endoscope images and so on could be involved in the film’s context.

The process seen as an end, , that is one of the methods for creators to possess their agency during the laborious process of image production, and to surf between the indigenous and western visual logic. Thus different “views” get to talk and reproduce their own value.

Film is a utopian vision of the creators. TFFUK, by introducing Taiwanese films to the UK, hopes to offer such a utopia a dialogue with audiences in other countries, for them to touch the future through a rich past. Katthveli invites creators to share their thoughts on film imagery. The themes include queer diaspora, political identity, female consciousness, aboriginal issues, image archaeology, and so on. This is a starting point for us to understand, in the context of Western modernity, how the creators are actively, unitedly, and politically conversing with the Other in European and American knowledge systems from these discrete and marginal perspectives. Film creation is a method for us to explore and expand the utopia within the imperial sound of “national” and “international” bangs.

No products in the basket.

No products in the basket.