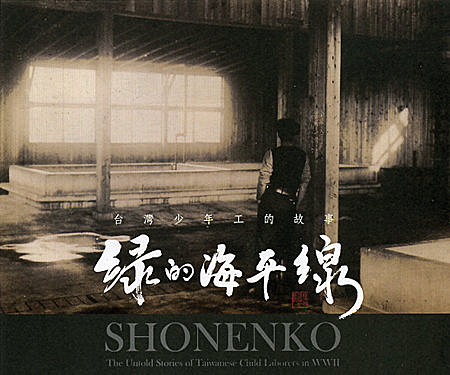

Shonenko (2006)

Shonenko, a film directed and produced by Liang-Yin Kuo, successfully demonstrates the epitome of documentary at a time when the production of documentary in Taiwan has tended to cater to popular trend and consumer taste. The film features a number of interviews, visual documents, information, and audio sources that constitute the historical records, trying to create a macroscopic historical vision with a microscopic approach. With concise visual narration and outstanding editing skills, the director utilised the recounts of the laborers who were young at the time, to reproduce historical experiences and memory, delivering messages full of self-reflection that go beyond the boundary between race, by clearly illustrating the complexity of multi-layered historical interpretations.

Shonenko shows a surprisingly high standard of the production of documentary in Taiwan. Liang-Yin Kuo values the exquisite but trivial fundamentality in her works, which is rare in documentary due to its desperate and lousy structure. For instance, the detailed interviews, the accurate counterpoint editing of various materials, the smooth camera movement, splendid soundtracks, exquisitely processed audio clips, and the elegant Taiwanese narration by Lim Giong all imply that the talent of the director is undoubtedly magnificent. With professionalism and a humble attitude, Kuo and her team created a role model for documentary filmmaking with impeccable quality.

The height of humanitarianism that the documentary presents is also venerable. Shonenko impresses the audiences with stories of the laborers that are told in a rational and calm tone, rather than overwhelming them with sensational tension to forcibly arouse their emotions. Thus, the audience is touched deeply by the historical story so that they are able to contemplate issues raised by it. Another element in the film, that marks an even higher level of humanitarianism, is its emphasis on the value of individuals in their grand history and tragedy, freeing those people from the judgment of morality and political effects.

For example, though being a strict Japanese teacher who forced Taiwanese students to ‘volunteer’ to work in Japanese-ruled Taiwan making airplanes, Takashi Tsu[not really sure the spelling here] cried during the interview while recalling the students who were killed by American soldiers in Japan. According to letters, some of the survivors still showed their love and respect for the teacher Takashi, demonstrating the essential kindness of human beings. The interviewee also recollected that the young Taiwanese laborers, who were supposed to be disbanded to their homeland, also cried along with Japanese after hearing of the failure of Japan. However, their tears indicated that they had foreseen the gloomy prospect of their life to which they had been dedicated, rather than being a symbol of the shift of national identity. Though Japan’s crime of its aggression and slaughter to Chinese is unforgivable, the film has taught us not to recklessly simplify the understanding of these situations and emotions with the binary concept of pro and anti-Japanese. Instead, we should understand the history from a more practical and individual experience.

The value of Shonenko as a history lesson was manifest in how it witnesses and traces part of the historical dilemma in Taiwan through the lives of young laborers. Director Kuo is brilliant at sending reflexive messages to the conflicting groups on the island through a seemingly objective and open-ended historical narration. For those attempting to reinforce the national identity of Taiwanese people by using this documentary, she reminds them that another group of Taiwanese who had desire for China (or the ‘motherland’) also existed. She doesn’t produce a documentary with an enlarged one-sided historical view like those desperate to cut ties with China do. Besides, Kuo reveals how the Kuomintang (KMT) regime tortures the Taiwanese after Japanese colonisation to mainlanders who are still blind to the history. [1] This documentary also provides the historical factors that explain the pro-Japan sentiment of numerous Taiwanese Hans and Hakkas. The reason why many Taiwanese people detest mainlanders and instead ‘miss’ the coloniser Japan is disclosed by the way the KMT are shown to treat the deported young laborers.

Shonenko doesn’t conform to the production logics of market-oriented documentaries like Elephant Boy and Robogirl and My Football Summer. Upon its 2006 release, it quietly and slowly demonstrated a rigorous and profound spirit of documentary. It prevents Taiwanese documentaries from being wholly demagogic and proves the quality that can stand the test of time.

[1] Here mainlanders (or waishengren in Mandarin) refer to the Chinese migrants who settled down in Taiwan following KMT’s defeat to The Communist Party of China in 1949.

Suspended Duty (2010)

Taiwanese society has a talent for forgetting its own history. I am uncertain about whether such a characteristic of collective forgetfulness or amnesia should be understood as a cowardly performance based on the fear of facing painful memories, a carelessness towards placing historical and political responsibility, or a pragmatic attitude of immigrant society that focuses only on the present moment. However, what I am certain about is that such disregard for history and memory is responsible for the formation of a profit-minded local political party that lacks of idealism, and its political counterculture. Hence, the Kuomintang regime, despite seemingly politically pure, yet has never actually being asked to or voluntarily face its historical responsibility, is made acceptable in Taiwanese society.

The most important value of Liang-Yin Kuo’s works, including in Searching for the Zero Fighters (2003), Emerald Horizon: Shonenko’s Stories (2006), and Suspended Duty: Taiwan Military Training Regiment (2010), is how she relentlessly pursues and investigates those historical moments that have been unsettled for so long they have almost diminished in memories through documentary. In these works, Kuo approached the history of the 1940s, a period when both sides of the Taiwan strait had experienced huge transformation, by looking into the individual statements and collective experience of common people’s life stories. These descriptions largely differ from those of people in power, in terms of documentary perspectives, problem awareness, and the basis of morality. The filmographic record that Kuo produced in order to reflect history and politics on a microscopic scale is invaluable. Moreover, her perseverance in examining and articulating Taiwanese people’s historical experience is undoubtedly a rare aura within this mostly practical, forgetful society.

Suspended Duty lively demonstrates the foul means that Kuomintang regime employed to call up men for military service in 1949-1950 by presenting the accounts of those who were forced to ‘voluntarily’ enlist. The Chiang regime recruited over 4,000 young Taiwanese males into the Army Sergeant Training Regiment through intimidation and bribery, only to realize the myth of recapturing China. Some of these men were enlisted as aircraft mechanics in Japan during 1943-1945, while others were sent to mainland China as Kuomintang’s mercenaries during the Chinese Civil War before 1949. Those who survived and return to Taiwan were then forced into military service again by the retreated Chiang regime in Taiwan.

These men were deprived of their rights to decide how to live out their lives while being forced into military. Even after being ‘suspended’ (a status that made finding new jobs almost impossible for them, since military discharge records were not provided), they were still under the political suppression of White Terror that prevented them from complaining at all. Sixty years ago, these Taiwanese men devoted their youth and lives to the state’s anti-communism myth and propaganda without any opportunities to articulate themselves. After sixty years, the regime that once valued anti-communism as its ultimate religious faith now comes hand in hand with Chinese Communist Party; they even address each other as brothers. How, if at all, may we then interpret the roles of these countless Taiwanese males that meaninglessly sacrificed their years of youth, some even their lives, for the state’s myth and lies in the military throughout the past sixty years? Has anyone ever seriously questioned the enormous collective loss and individual scarification based on the joke made by the ‘state’?

This is the exact manifestation of the pragmatic, careless characteristic of the Taiwanese society. Kuo, as a young female filmographer, with her own strength investigated into every detail, refused to forget, and insisted on the importance of human lives and dignities as the foundation of significance. The significance of an individual has to come first before the state. If the state or government ignored and neglected the existence and significance of individual, they shall become illegitimated. Just like her former work Emerald Horizon (2006), Kuo conveys a reflective, anti-war message that largely criticises militarism through a calm, serene tone in Suspended Duty. The film also reveals through interviews how military victims, despite coming from different ethnic groups, manage to surpass ethnic prejudices, and are finally able to sympathise and understand each other. By employing several humorous expressions and investigating a tough issue with a brisk tone, it perfectly balances on the calibration of its paces and emotions.

The film name is translated into Suspended Duty, which contains multiple layers of in-depth meanings. This is a story of the Cold War victims whose youths were eternally dismissed by the state. Such an unjust government has never confronted its unfinished duty. However, we must thus ask ourselves, shouldn’t we consider the presence of such irresponsible state and government as the very result and responsibility of our collective forgetting, inarticulate society that has never looked back and examine our history?

No products in the basket.

No products in the basket.