One could say that it is something of a tradition in Taiwan to engage with sensitive political matters through film. This began with the Taiwanese New Wave and has continued to the present.

First-generation Taiwanese New Wave director Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s 1989 City of Sadness, for example, was the first film to depict the 228 Massacre, which left tens of thousands dead in 1947. The film was released at a time in which discussing Taiwan’s authoritarian past was still a sensitive, even dangerous political issue and the film was released one year before the outbreak of the 1990 Wild Lily Movement, a seminal moment in Taiwan’s democratization.

LGBTQ issues became prominent in the films of second-generation Taiwanese New Wave directors. Ang Lee’s 1993 The Wedding Banquet is thought of by many as the first film to address LGBTQ issues head-on in Taiwan, the film focusing an interracial gay couple living in New York.

The film presented queer issues through the lens of a comedy, perhaps as a way of naturalizing gay relationships and queer desire. However, the film also grappled with issues regarding the clash of traditional “Chinese” values revolving around the heterosexual, multi-generational family, as in the notion of “Three generations under the same roof” (三代同堂), versus homosexuality, framed in some way as “western” and something introduced to Taiwan through outside influences. The film’s conclusion can be thought of as suggestive of the potentials of queer, non-heteronormative, and non-dyadic family units, such as the three-parent family. The Wedding Banquet is the first of three Ang Lee movies featuring gay characters to date, the most famous of which is probably Brokeback Mountain.

The Wedding Banquet was followed by Tsai Ming-Liang’s 1994 Vive L’Amour, which about three strangers whose lives intersect because they secretly inhabit the same unoccupied apartment. The film addresses queer alienation, setting this at the foreground of the film by beginning with its first protagonist, Hsiao-Kang, attempting to kill himself because he is gay. Hsiao-Kang’s thwarted desire presents itself in various ways throughout the film. Tsai himself being openly gay, queer themes have resurfaced in many of his films, particularly regarded desire, voyeurism, and alienation, though Tsai more often features a gay character among a larger cast than does he focus entirely on gay characters.

It is probably best to see such films as calculated risks in tackling controversial subject matter rather than necessarily as directors boldly using film as a medium as to speak truth to power. The reason why such films are remembered today is, after all, because such films were commercial and critical successes, even during the times in which they were released.

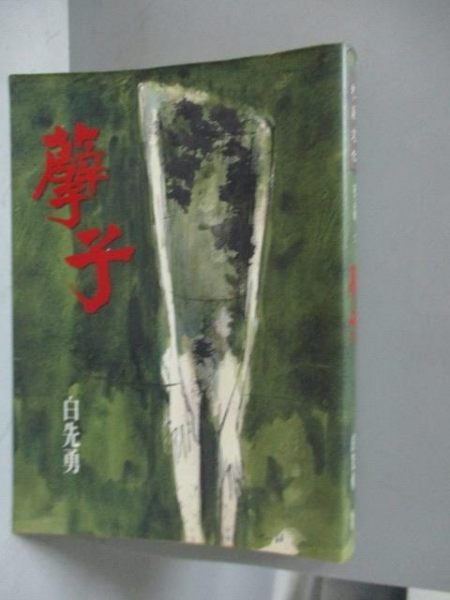

But these films have played a crucial role as to why Taiwanese films have continued to address queer topics. Taiwanese New Wave films played a disproportionate role in shaping what the perception of Taiwanese film was internationally and it still does. Yet insofar as “Taiwanese film” became thought of along certain parameters, with certain recurrent thematics, addressing queer issues was one of them. This was perhaps parallel to developments in literature at the time in Taiwan, with the emergence of queer writers in the 1980s, and Taiwanese literature subsequently thought of among “Sinophone literature” as having prominent queer themes. An early work such as Pai Hsien-Yung’s 1983 novel Crystal Boys, seen by many as the first Sinophone work to address queer themes, and the emergence of other gay and feminist writers in the 1980s and 1990s, overlapped with the emergence of the Taiwanese New Wave filmmakers.

The Taiwanese domestic film industry collapsed with the entrance of Taiwan to the World Trade Organization in 2002 and the influx of American Hollywood films that followed, but with the revival of Taiwanese domestic cinema in the years since the 2008 hit Cape No. 7, one has seen the revival of Taiwanese queer film as well. Much as New Wave film were powerfully shaped by the turbulent times of Taiwanese democratization in which it emerged, the revival of Taiwanese cinema is shaped by the age of social movements that began in 2008 with the Wild Strawberry Movement. One can discern two distinct tendencies in the queer films which have been released since 2008: Fiction films and documentary films.

Contemporary Taiwanese fiction films may not have yet hit upon a distinctive visual language in the way that the shared visual language of Taiwanese New Wave films saw them generationally grouped together by international critics. There has been, for example, no “Third-Generation New Wave” or other label coined to group together contemporary Taiwanese filmmakers. However, one notes that the current generation of Taiwanese film often reflect decidedly contemporary social concerns. The 2017 film Alifu, the Prince/ss concerns itself not only with transgender issues but also issues regarding indigenous cultural identity, through its trans and indigenous protagonist, the eponymous Alifu.

In particular, indigenous issues have become widely discussed in Taiwanese society after Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-Wen’s historic apology to Taiwanese indigenous on behalf of the government in 2016, shortly after Tsai took office, and protest by indigenous groups of the government’s failure to return traditional territories to them afterward. Likewise, Tsai was elected into office on promises to legalize gay marriage, leading to an increased focus in queer issues since 2016 and this is also reflected in film.

Since 2008, there has also been a boom in documentary production in Taiwan, with filmmakers hoping to shed their light on various social issues. Yet another characteristic of contemporary Taiwanese documentary is the director’s strong subjective presence in the film, with many documentaries focusing on a subject in which the director is implicated in some way, or the documentary gradually morphing to also become the story of the director.

The most famous of these films is no doubt the 2016 documentary Small Talk, directed by Huang Hui-chen, executive produced by no less than Hou Hsiao-Hsien, and in part scored by Lim Giong, a pioneer in both the Taiwanese pop-rock of the 1980s and contemporary experimental electronic music. Lim has scored or acted in many Taiwanese New Wave films. Small Talk concerns itself with Huang’s relationship with her lesbian mother, and was Taiwan’s submission to the Academy Awards in 2016. The involvement of Hou and Lim point to the direct links between contemporary Taiwanese queer films, inclusive of documentary film, and the Taiwanese New Wave, in some ways.

At the same time, there also a tradition of directors in Taiwan setting down their cameras and directly involving themselves in political activism. Sometimes this is through advocacy, with directors speaking up for LGBTQ causes. In large part, society is receptive to such advocacy is because of veneration for directors as auteurs in society. This can vest even small actions by directors with a great deal of social significance. For example, shortly before the referendum on gay marriage held at the end of November 2018, a picture of a piece of paper with the words “Love Above All” went signed by Ang Lee viral on social media, seeing as this was Lee, as a respected director who represents Taiwan internationally, expressing his support for efforts to legalize gay marriage in Taiwan.

A number of directors whose films are concerned with LGBTQ-related topics have been vocal on queer issues as well. To name a few examples, Small Talk director Huang Hui-chen has been vocal in her support for gay marriage, appearing in a number of livestream shows about gay marriage to try and raise awareness of the issue. Director Zero Chou is herself openly lesbian, and has produced a series of films for LGBTQ-focused Internet platforms such as Gagaoolala, including films as The Substitute, We are Gamily, and the Six Asian Cities Rainbow Project, featuring LGBTQ stories from six cities across Asia.

Other times, directors will even take on a leadership role in movements themselves. The 4-5-6 Movement, for example, was a weekly anti-nuclear demonstration that took place for two years starting from 2013, organized by a group of film and documentary directors led by New Wave director Ko I-Chen. Though the demonstration was not directly about LGBTQ issues and was specifically focused on the issue of nuclear energy in Taiwan, the protest hit on a number of broad-ranging social issues, including that of gay marriage, and members of LGBTQ advocacy groups were often invited to speak at the event.

Other members of the film industry have sought to directly enter politics. Neil Peng, the scriptwriter for The Wedding Banquet, as well as a comedian, and talk show host ran for mayor of Taipei in 2014 as an independent. However, despite writing the script for The Wedding Banquet, Peng has also been known to make homophobic slurs against former president Ma Ying-Jeou in the past, alleging that Ma and National Security Council secretary-general King Pu-tsung were lovers.

However, concerns regarding why Taiwanese queer films and documentaries gain international circulation is a question worth pondering in itself. Certainly, there is the aspect of their “foreignness” as Asian films or films perceived to be a variant of Chinese cinema which leads to such films gaining circulation.

As with the queer films of Taiwanese New Wave before it, in which international critics primarily saw such films through the framework of being the first “Chinese” films to engage with taboo topics as homosexuality, this may also be the case with latter-day Taiwanese documentaries or film. This seems to be one of the reasons for the widespread international appeal of Small Talk, for example, given that Huang’s mother is not only lesbian, but also a Taoist priestess. The strong Chinese cultural aspect of this may be a selling point for international audiences and may have contributed to the popularity of the film on the international film festival circuit.

This is particularly salient as an issue because, after the Tsai administration’s promises to legalize gay marriage in 2016 election campaigning, Taiwan has been widely spotlighted in international media as potentially being the first country in Asia and the first “Chinese-speaking territory” to legalize gay marriage. And this has led to a renewed interest on Taiwanese queer cinema, television, literature, and other forms of Taiwanese cultural production as potentially reflective of the socio-cultural particularities that could lead Taiwan to potentially become the first country in Asia to legalize gay marriage.

Yet at the same time, this raises accusations that Taiwan has embraced queerness as a form of homonationalism. This would all the more be the case because Taiwan is not acknowledged by the majority of the world’s countries as a nation-state, and it is politically claimed by China as a part of its territory. Claiming that Taiwan differs from China because it has legalized gay marriage and is LGBTQ-friendly, as visible in Taiwanese queer cinema, could simply be the commodification of queer cinema, then, and a way of subordinating this to a national cultural project. This seems to have been the Tsai administration’s primary aims in advocating gay marriage, for one, as a means of distinguishing Taiwan and China, although after widespread protest from anti-gay groups, the Tsai administration gave up open advocacy on the issue.

Any effort to critically engage in the history of Taiwanese queer cinema must then, address this, so as to avoid simply being a facile attempt to claim the history of queer cinema in Taiwan as authentically and quintessentially “Taiwanese” merely for the sake of homonationalist identity construction. We will discuss this issue further in following articles.

No products in the basket.

No products in the basket.