Over a year, Taiwanese filmmaker Tsai Ming Liang has shown the flexibility and potential of his film world through two works.

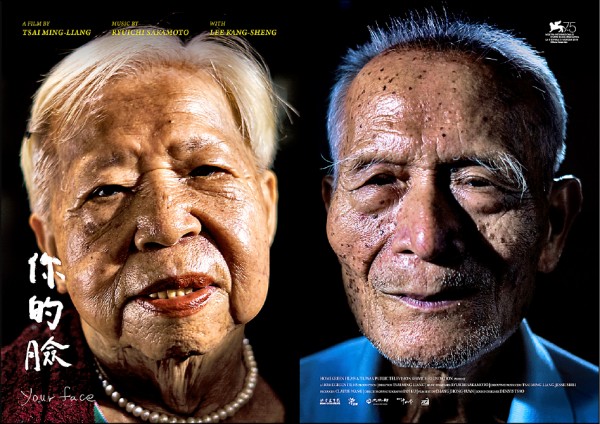

VR-film The Deserted (2017) leads the audience into a seemingly normal but somewhat ambiguous world. No matter how much the audience wants to examine the story, they can’t get close to it. Being on the spot doesn’t mean there’s no distance. In contrast, it’s a bizarre mixture of remoteness and broken pieces, as if there is a patch of light fog between us and a piece of glass; it seems so close, yet unreachable. His new work, Your Face (2018), on the other hand, goes to another extreme: close-ups of thirteen faces is the core of the movie. One is virtual, and the others filled with real shots. They both take time as a bet; the human figure transforms into two types of images.

The flexibility and potential of Tsai Ming Liang’s movie world, taking The Deserted and Your Face as examples, are the epitome of the relation between “Time” and “Figure” explored in his art of moving image over the last 30 years. Long takes are divided into two; one focuses on the figure, while the other gazes into the face.

Long Takes of Close-ups. More than Picture and Photography

Indeed without The Deserted, which made it feel necessary for the director to focus on the face, close-ups in Your Face wouldn’t have been created. Tsai went back to Ximending in search of suitable actors, as in previous years when he was making sitcoms or movies. This time, around ten passers-by in their 50s and 60s caught his eye. After negotiation, the director decided to shoot the film in Guangfu Auditorium (光復廳) in Zhongshan Hall. Tsai Ming Liang took several days to design the lighting and composition for every actor himself; each shot took about 25 minutes. The camera focused on their faces, each has their own story to tell, with some people looking around, some remaining in silence, some motionless, some laughing, some falling asleep, some lost in memories, some weeping, some talking with the director and randomly rubbing their face, and some playing the harmonica. As the movie is composed of close-ups, it’s an extension and succession to picture and photography that records the subjects’ expression and posture. Meanwhile, the movie, beyond picture and photography, is not only a documentary of the face, but the hourglass of life. Every story from each person’s face, besides reflecting the physiognomy, tells the passage of time and the journey the subjects have made: from the subtle changes in facial expression to mentions of the past and how life shifts is touched by a momentary silence. The faces of the movie tell the passage of time; the stories belonging to each face form a landscape of their personal histories.

Face as Face. Capturing Random Moments

The Deserted unexpectedly led to the production of Your Face, a special case for a director like Tsai Ming Liang, who emphasises the modernity of cinema in a post-movie era. Your Face has a profound meaning to any movie lover who would associate it with the art of silent film and modern cinema history. Masterpieces such as D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms (1919), Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), Jean Epstein’s Bonjour Cinéma (1921), Béla Balázs’ Visible Man (1925), Bergman’s Summer with Monika (1953), Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959), and Godard’s Breathless (1960), all indicate that the close-up embodies not just cinematic power, but also the spirit of a film. In Your Face, large close-ups of over ten ordinary people are presented in a single shot. It records deep emotions; each face is reconstructed alongside lighting and music.

Close-ups allow for inspection; this is the core value of Tsai Ming Liang’s film. The director searched the streets for actors he wanted. Between him and those he encountered is a shared once-in-a-lifetime connection, like in 1991 when the director came across Lee Kang Sheng. Between the eyes and face; between myself and another, image ethics, or questions of image ethics, are inevitably built up. Meanwhile, the intuitive, improvisatory, and occasional arrangements, the values that movie modernity has been seeking, were spontaneously constructed through both the eyes of the director and the faces of the actors. Thus, the meaning behind the title “Your Face” is found. The concept “Face as Face” establishes the first layer of meaning before casting and filming.

Face as Surface. Reflection of Surging Emotions

Tsai Ming Liang is responsible for every single face. Within a number of minutes, the gaze between the director and the actors reveals what’s been concealed and forgotten. For Tsai Ming Liang, however, the value of the close-up doesn’t lie in what the subject says (he spent several months cutting off the actors’ narration, making the film less documentary-like), but how each face is shown. Thus, what makes Your Face enchanting is how each face is lit. From a front to a side view, each face has dramatically sculptured features; visualised and formed through the carefully devised lighting. The close-up of Lee Kang Sheng, whom Tsai Ming Liang is most familiar with, comes no doubt as a surprise, with the left side of his face covered in light, while the other side shadowed. While Tsai insists that his film isn’t a documentary, I feel that this statement isn’t so much about film categories, but instead related to his intention of recreating a certain type of film power, which could be associated with silent film or modern film, or beyond categories such as documentary, drama or experimental. The concept “Face as Surface” on one hand, indicates the expressions and changes on the actors’ face; on the skin, while on the other, it means the face can detach itself from the body, and become part of the image: the face is where the light centres on, and where the story of the film is formed.

Face as Interface. In Honour of History of Film

It’s worth mentioning that throughout the parade of faces play ten soundtracks composed by Ryuichi Sakamoto that give a crucial touch to the movie. It’s like a gentle breath of air that touches a cheek and stirs up emotions; with the lighting and composition, the soundtrack sketches the close-ups of the actors, forming the outline of Your Face. As Tsai Ming Liang believes in modernity, he aims to immerse the audience in 77 minutes and 13 faces, wrapped up with the long-held shot of an empty ballroom and shifting light. Considering the director’s statement that Your Face is not a documentary, the camera and the screen are not just about images, but a mirror or a shifting piece of glass. The question arises: am I looking at myself or someone else? Am I being watched? “Face as Interface” transforms into a mirror of metacognition, by which Tsai pays his homage to movie history; actors face actors, the audience faces the actors, and the audience themselves.

Are you staring at me? Your Face returns to the close-up of filmmaking, in search of the vanished vision.

No products in the basket.

No products in the basket.